Interlude in Blue #2 – Making the Blue

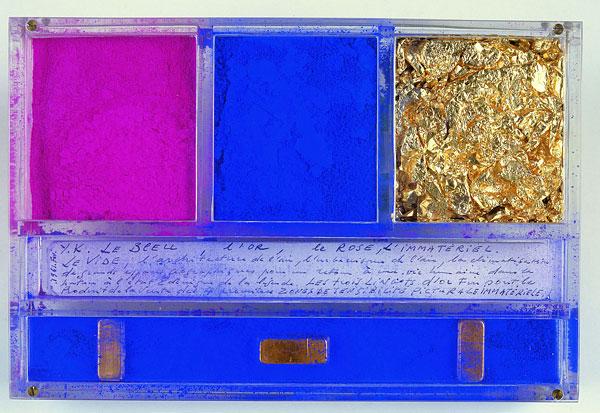

Crushed lapis lazuli, or ultramarine pigment. This photo actually appears a bit duller than synthetic ultramarine. It may be due to lighting, or it may be not be from impurities in the stone. Powdered, synthetic ultramarine appears so vibrant, that Yves Klein, a French artist in the 1940s, became obsessed with reproducing a paint that could retain the appearance of the powdered pigment while suspended in a medium and after years of experimentation, was able to achieve the effect and was able to patent the process and color International Klein Blue was named for him. It should be noted, that Klein’s preferred and patented method for painting was to cover models in pigment and direct them to move on a large canvas. Here a two of Klein’s three dimensional works, that really show the vibrancy of the color better than his body paintings.

Large Tree with Sponge – 1962

Synthetic ultramarine. (Sometimes called French Ultramarine)

French Ultramarine

In the early 1800s the prohibitive cost of natural ultramarine pigment motivated first the Royal College of Arts in Britain and a few years later, the Society for the Encouragement for National Industry in France to offer cash prizes to anyone who could actually produce an artificial that was chemically identical to the pigment made from lapis. At the time, natural ultramarine was selling for a little over eight British Pounds to the ounce, while gold went for a little over four. By using the byproducts of glass furnaces, chemists in both Germany and France were able to produce the synthetic ultramarine, and despite the variety of places of discovery, the product came to be known as French Ultramarine. This is the blue that the impressionists used most of the time, Renoir in particular, although they sometimes also used another synthetic blue, Prussian Blue, which tends to have a more greenish and less vibrant tint and was used more often to mix with yellow to produce greens.

Those Prussian Fucks

Thru out the book you’ll find The Colorman referring to those “fucking Prussians” and spitting. You see, until the mid to late 1800s, there were still many rare and difficult to obtain pigments being used. National policy was often changed just because of, say, the inability to get enough dye for the uniforms of a country’s army. Then along came the German chemists.

Around this time, most of the world’s major cities were being lighted with gas. But not natural gas as we know it, drilled and piped from the ground, but coal gas. As central boilers, large quanties of coal were more or less cooked, under pressure in large metal vessels, and as a byproduct of their heating they gave off burnable gas. The distillation of coal also produced a byproduct called coal tar, which was produced in quantities that really became unwieldy. German chemists, using coal tar, developed processes to produce vivid, permanent, and largely non-toxic artificial pigments, which undermined the market for the rare, natural pigments prized by painters and color men. (Their production also turned the Germans from a largely agricultural country to a manufacturing powerhouse.) Between that and the movable type printing press invented by Gutenberg, leading the way for reproduction of information and images, the Germans (Prussians) they pissed the Colorman off.