Chapter 5 – Gentlemen with Paint Under Their Nails

The Salon des Refusés There’s a whole political story behind how the Salon des Refusés and how it’ssort of interestingly but indirectly tied into Cinco de Mayo and even the Civil War, which sort of connects back to Whistler and Manet’s painting careers, but, well, people use the phrase “sort of” as much as I do, really shouldn’t be writing history, so I’ll let you click the link and I’ll come back and fill in here later if I have time. Now for the chapter.

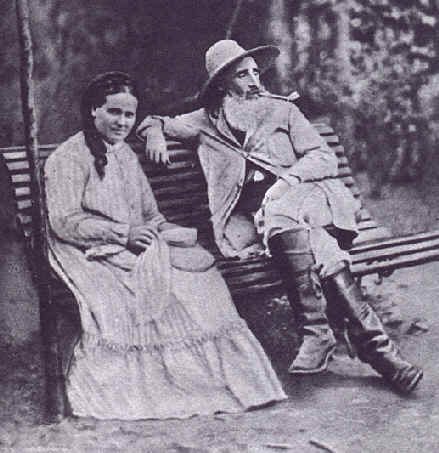

Camille and Julie Pissarro, around the time of the scene 1863

“Machines of the rejected,” said Pissarro, for once a note of despair dampening the Caribbean lilt in his accent.

Pissarro and Julie were living with her mother at the foot of Montemartre at the time. Artists, writers, musicians of the time would refer to their works as “machines”, making it a generic way to discuss a work of art. So Emile Zola, an novelist, might discuss his latest “machine” with his friend, Paul Cezanne. Perhaps it was the Industrial Revolution, and the sudden mass production of pottery and other objects that had always been made by hand, but were now being made my machines, that was the source of the term.

“They moved into the column of people that was squeezing itself into the palace: the upper-class men in top hats, black tailcoats, and tight gray trousers, women in black crinoline or black and maroon silk, their long skirts dusted at the fringe with white from the macadam; the new working class, men in white and blue striped jackets and straw boaters, the women in bright dresses of every color, sporting frilly pastel parasols, the mandala of the Sunday afternoon of leisure, a recent gift of the Industrial Revolution.”

Music-in-the-Tuileries-Gardens-1862 -Eudoard Manet

Manet meant here, to show Paris at leisure. This would be a Sunday Afternoon among the upper class in the park, probably a very similar looking crowd to what would have been at the Salon de Refusee. The Jardine des Tulaeries (Tuleries Garden), is, in fact, a palace garden.

“Excuse me, Monsieur Manet,” said the tall man. “I am Frédéric Bazille, and these are my friends—” Portrait of Frederick Bazille by Pierre August Renoir – 1867

“The painter Monet,” said the youth with the lace cuffs. He clicked his heels and bowed slightly. “Honored, sir.” Portrait of Claude Monet by Pierre August Renoir – around 1875, so the Monet at the Salon will a younger, possibly fancier Monet.

“Renoir,” said the thin fellow with a shrug. Self-portrait of Renoir – Pierre August Renoir – 1876

“Well she’s not wet,” said the woman. “This is not a picture of bathers. Looks to me like she’s deciding which of these two she’s going to bonk in the bushes.” Dejener sur le Herb (Luncheon on the Grass) -Edouard Manet – 1863

“Perhaps we’ve happened onto the scene before the bathing,” said Manet. “The motif is classical, madame. After Raphael’s Judgment of Paris.”

Actually, the painting Manet probably was inspired by was the above, Giorgione’s Fete Champetre – 1508. (Feast in the Fields)I probably read the Raphael bit from above, and didn’t find the actual painting. The problem wasn’t that no one had ever painted a naked picnic before, it was no one had painted a modern, “real” picnic. You just didn’t do such things. Anyway, by the time I figure this out, it was too late to change the line in the book. Oops.

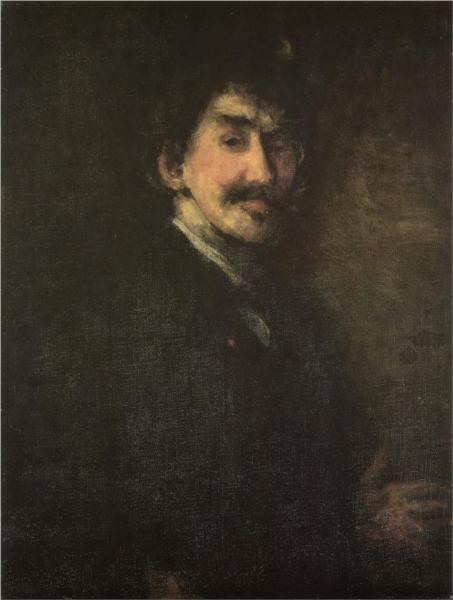

He was a gaunt, dark-haired fellow about the same age as Manet, with an outrageous gondola of a mustache riding his lip and a monocle screwed into his eye like the brass porthole of a warship. Arrangement in Gold and Brown – Self Portrait. James McNeill Whistler

“Ah, Mother,” said Whistler in English. “She’s an arrangement in grey and black; her disapproval falls like a shadow across the ocean. And yours?” Arrangement in Grey and Black #1– James McNeill Whistler – 1871

Even though Whistler isn’t completely into his Oriental phase yet, you can see how the picture could almost be overlaid with a Yin-Yang symbol. The perfect balance of object and space. That’s Zen composition, not the “rule of thirds” taught in Western painting.There’s a revolution brewing in painting, and Manet and Whistler, although they don’t know it at the time, are at the forefront.

“My White Girl. She was turned down by the Salon and the London Academy. Her name is Jo Hiffernan said Whistler. “An Irish hellcat—skin like milk. Quick-witted for a woman, and a soul as deep as a well.” Wapping on Thames – 1860-64- James McNeill Whistler – I don’t know why this one wasn’t retitled to a music arrangement theme, perhaps because it was before he felt that approach applied to his work. Perhaps the National Gallery in Washington wasn’t going to put up with Whistler’s tomfoolery. Nevertheless, you can see this painting of Jo and some of Whistler’s friends, at the National Gallery, about twenty feet from Symphony in White #1- The White Girl

“All that lead white soaks right through your skin. I still see rings around every point of light. My doctor says it will take months for my vision to return to normal.”

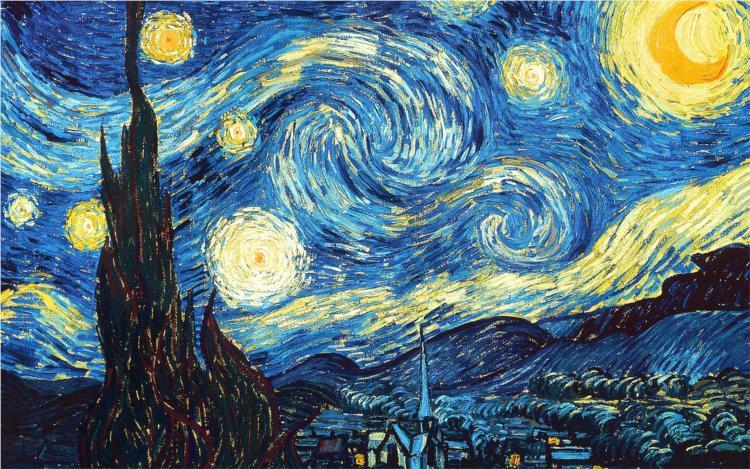

Seeing swirls around light sources is an actual symptom of lead poisioning, which Whistler actually suffered. In reality, his White Girl was at the Salon de Refuses, but he was not. He was still in Biarritz getting over his lead poisoning and, yes, getting smashed by a rogue wave. That too is a true story. But the reason you’re looking at Starry Night, by Vincent Van Gogh-1889 – Because of the swirls in this painting, and his notorious habit of eating paint, one of the diagnoses in retro that doctors have made is that lead poisoning may have exacerbated his other physical and mental difficulties.

“Jemmie, this White Girl of yours wasn’t the painting you were working on in Biarritz when you had your accident, was it?”

“No, of course not. That was in the studio. The Biarritz painting was called The Blue Wave.“ Arrangement in Blue and Silver – The Blue Wave- Biarritz – 1863 “Arrangement” is the revised title of The Blue Wave. In the 1870s, Whistler befriended a composer, and after discussion of their “machines,” he retitled all of his paintings as musical compositions. So his White Girl became Symphony in White #1, and The Blue Wave became Arrangement in Blue and Silver, the painting known commonly as Whistler’s Mother was never titled that. He painted it after he had started titling his work after music, so it has always been Arrangement in Grey and Black #1.