Chapter 19 – The Dark Carp of Giverney

It was two hours on the train from Gare du Nord to Vernon, and during the ride Lucien sat near a young mother and her two little daughters, dressed as finely as fancy dolls, who were traveling to Rouen.

From the station at Vernon, he walked the two miles into the countryside to Giverny —

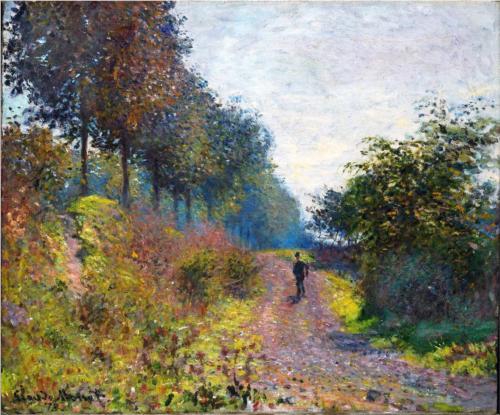

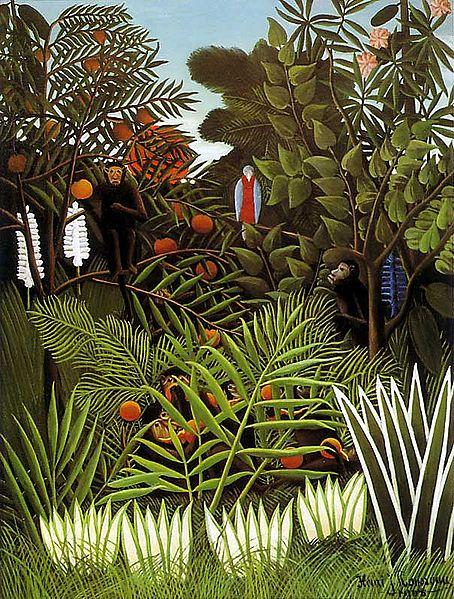

The Sheltered Path – Claude Monet – 1873

—less a village, really, than a collection of small farms that happened to perch together just off the river Seine.

Lucien walked through the back garden, rows upon rows of blooming flowers, built from the ground up on trellises and tripods

This was a garden designed by and for a painter, someone who loved color.

He came out of the mounds of color and–

–into a cool grove of willow trees, and there, by the two mirror-calm lily pond

–he found Monet at his easel.

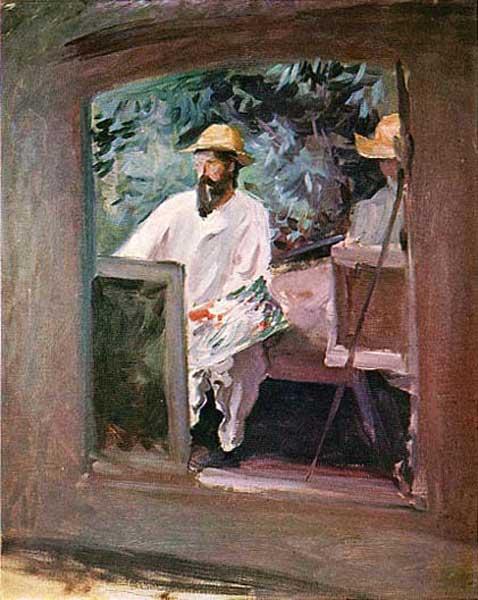

This is painted about the time of the story. It’s not exactly appropriate for this description, since Monet is working on a canvas that’s on the ground, not an easel, but it’s fairly clear here that Monet is painting with another painter. By this time, he (was well as Cezanne) were painting with pilgrims who were coming from all over the world to paint at the side of the master. Sargent was an amazingly successful American artist who went to France and painted with Monet. There’s a wealth of Sargents in the Boston Museum of Fine Art where he painted the murals and The National Galleries in Washington. He made his reputation painting portraits of the wives of royalty and business magnates. He had the ability to embue the subjects of his paintings with an inner light, and I’m yet to see a Sargent portrait of a woman in which he does not find the beauty in his subject and make it shine.

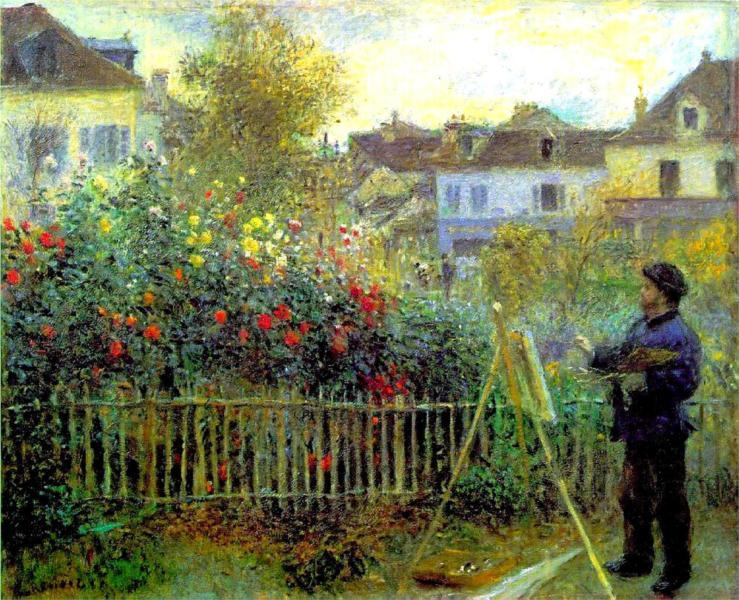

Here Monet is much younger, in 1873, in his garden at Argenteuil, another garden he built to be painted, and at this point in his life, when he was nearly completely broke.

Monet had become so engrossed in his work that he’d neglected to notice a team of athletes had come to the field to practice, and so had been quite surprised when an errant discus shattered his ankle. Bazille had painted the scene of Monet convalescing, his leg in traction.

This is a true story. Fortunately, Bazille was a doctor, so he was able to set up his friend’s traction before stepping back and making this painting.

My wife, Camille. It was Camille who brought it to me, and it was she who paid for it.

Camille Monet Reading – Pierre-August Renoir – 1872

Renoir painted Camille Monet many, many times. Strangely, in most of his paintings, as well as those that Monet made of her, Camille is wearing blue.

“My wife slips away and I am painting her corpse. I told her I had to capture the shade of blue Camille was turning, before it went away.”

Obviously, part of this anecdote is true. (The capturing of Camille’s image on her dead bed.) This, almost more than anything else, made me realize how Claude Monet was first and always a painter. This single-mindedness of purpose and identity may be behind what made him the leader of the Impressionists. Not a need to promote himself, or be in charge, the way Degas apparently did, but just his identity as a painter and his passion for capturing light and color in a moment on canvas.

“The Colorman is like that carp, Lucien. In all of our paintings, Pissarro’s, Renoir’s, Sisley’s, Morisot’s—even poor Bazille, before he was shot in the war—even back then, from the first days when we all met in Paris, he is there, in all our art, just below the surface.”

The dark carp of Giverney. I found him the way that Monet describes. He’s well-lit here, but in most cases, you can’t even see him until he moves. He’s beneath the reflections, the colors, the surface. He was an amazing, muted, contrast to all the color and light of Monet’s garden.

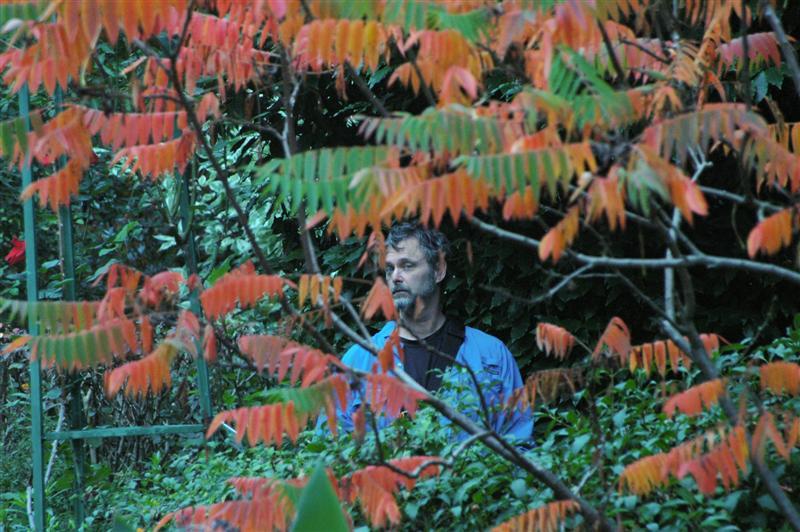

The Author Guy lurks among the foliage of Giverney, like a dark carp hisownself.

The Colorman had entered through the Catacombs’ entrance at boulevard Saint-Jacques.

I’d have pictures of the catacombs, but they were closed the day I went there.

(Photo by Ken Fricklas – your humble webmaster ) Blow up of the sign, below.